Do Corporate Jobs Evolve Like Living Organisms?

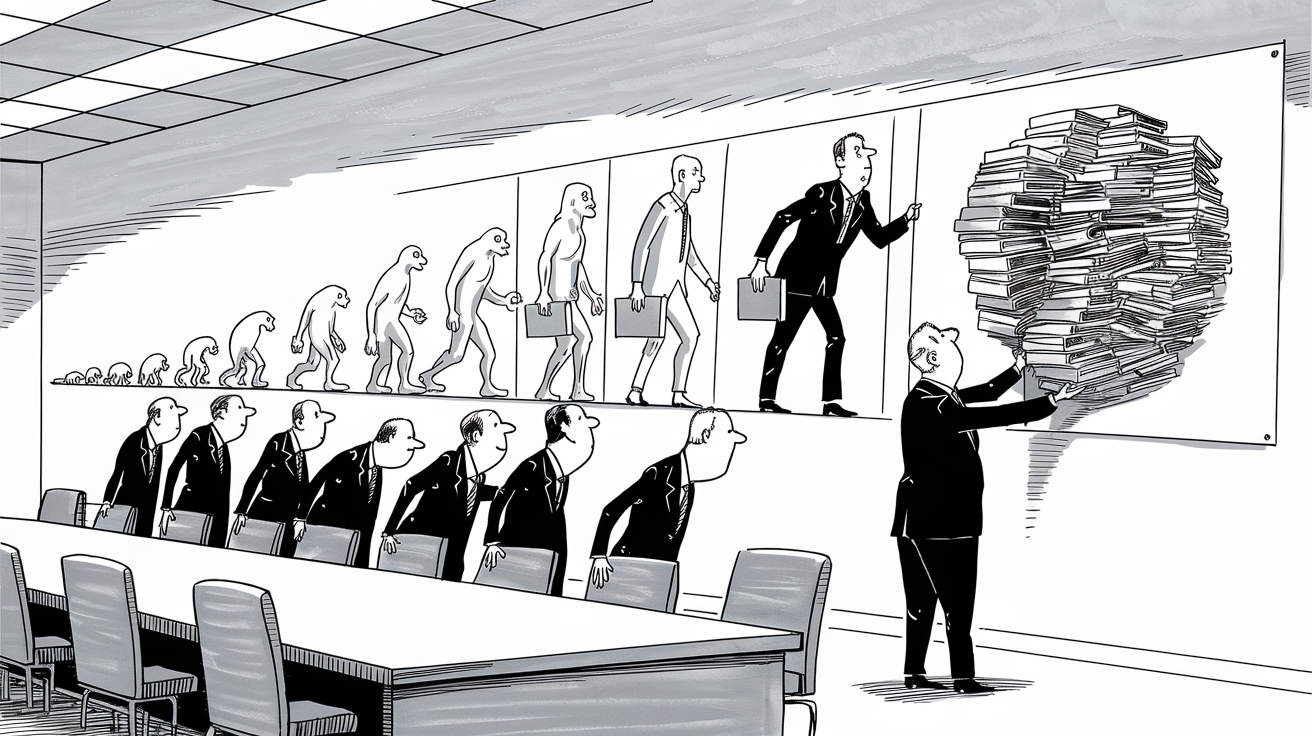

Survival of the Office: How Corporate Jobs Evolve to Perpetuate Themselves. Many modern corporate office jobs give the impression that they exist less to maximize productive output and more to ensure their own ongoing existence. This view suggests that some roles and bureaucratic structures in organizations behave like self-sustaining organisms, persisting and even expanding independent of the value they create. Using analogies from biology and evolution, we can explore how workplace behaviors and job structures mirror "survival of the fittest" dynamics - not necessarily the fittest at producing results, but the fittest at ensuring survival within the corporate ecosystem. This perspective raises intriguing questions: Are some jobs adapted to thrive by appearing indispensable rather than by being efficient? Do organizations unwittingly select for behaviors that preserve the status quo? By examining corporate life through evolutionary psychology, behavioral economics, and organizational theory, we can better understand these phenomena and consider how to realign workplaces toward genuine productivity and growth.

The Selfish Gene and the Selfish Job

In evolutionary biology, Richard Dawkins' "selfish gene" metaphor portrays genes as replicators focused solely on their own continuation. By analogy, we can think of certain jobs or departments as "selfish" roles - structures that evolve primarily to preserve themselves. Just as genes propagate without conscious intent, a corporate role can take on a life of its own. Over time, its processes and routines become self-perpetuating, even if the original purpose of the job has faded. In bureaucratic slang, this is often described as a "self-licking ice cream cone" - a self-perpetuating system that has no purpose other than to sustain itself. Such a job or department continually justifies its existence by creating work for itself, much like an organism ensuring its replication.

Organizational theorists have long observed this self-sustaining dynamic. Pournelle's Iron Law of Bureaucracy captures it succinctly: "In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control," whereas those dedicated to the organization's actual goals "have less and less influence" and may even be pushed out over time. In other words, roles that focus on preserving the bureaucracy's continuity tend to thrive. The "mission" of the organization can become secondary to the mission of the bureaucracy to keep itself going. Employees who excel at protecting and expanding their departmental turf (rather than, say, innovating or increasing output) often rise to positions of influence. The survival instinct of a job function can thus override its original functional mandate, akin to a gene mutating to favor its own replication.

This self-preservation tendency explains how corporate processes can turn inwards. Meetings beget more meetings; a report that once justified one analyst's job may evolve into a whole reporting team. Like DNA copying itself, a single role can replicate into an entire layer of management. The result is an organizational structure full of feedback loops that reinforce the importance of its own existence. At its extreme, the bureaucracy becomes an organism, one that consumes time and resources to maintain itself, sometimes with only a tenuous connection to the productive outcomes it was meant to deliver.

Survival of the Fittest (Employees) in the Office Ecosystem

Charles Darwin's idea of "survival of the fittest" in nature refers to organisms best adapted to their environment surviving to reproduce. In a corporate office environment, "fitness" takes on a different meaning: the employees who survive and advance are not always the most productive in terms of output, but those most adept at navigating the office environment. The "fittest" employees in a bureaucratic context are often those who adapt their behavior to appear indispensable. This can involve savvy office politics, careful alignment with superiors' expectations, and visible displays of activity - even if those activities are not objectively useful.

In evolutionary terms, employees exhibit adaptations for self-preservation. For example, consider the widespread behavior of "looking busy." Many employees consciously or unconsciously engage in impression management - coming in early or staying late, sending late-night emails, or cc'ing managers on trivial communications - all as signals of dedication. These behaviors are modern workplace analogues of survival strategies. Just as certain animals develop camouflage or elaborate displays to secure their survival, employees develop ways to signal their indispensability to the "tribe" (their team or company). A recent workplace survey found that 32% of employees admit to "faking work" at times - for instance, deliberately stretching simple tasks or populating their calendars with pseudo-meetings - in order to appear busier and more essential. Such tactics are essentially adaptive behaviors in a competitive office ecosystem where being seen as idle could mark one for downsizing. The same survey noted that even managers are not immune: over a third confessed to faking productivity at times, indicating that from staff to leadership, individuals feel pressure to perform busyness when actual work is lacking.

Office politics also illustrates survival of the fittest in action. In a stable or stagnant corporate environment, the qualities that help an employee survive may be political savvy, network building, and risk-aversion, rather than creativity or efficiency. An employee who openly challenges inefficient norms or tries to innovate may find that such behavior, while good for the company's output, threatens entrenched interests - and thus the organization's "immune system" might reject them. Meanwhile, an employee who nurtures alliances, avoids controversy, and takes care to credit those above them can sail smoothly. This dynamic aligns with evolutionary psychology: humans evolved in groups where social acceptance and status were key to survival, so we are wired to seek security and approval even at the expense of short-term task effectiveness. In a corporate setting, this can translate to a strong status quo bias - people stick to established routines that signal competence, rather than experimenting with unproven but potentially better methods, out of fear of rocking the boat. In evolutionary terms, the cost of sticking out (and possibly being expelled from the group or losing one's job) often looms larger than the potential benefit of a breakthrough. Thus, cautious survival strategies win out.

Behavioral economics provides a complementary lens: employees often face a principal-agent problem in which their personal incentive (to keep their job secure) diverges from the company's incentive (to maximize performance). If the company's reward systems don't perfectly align output with recognition, employees rationally focus on what does secure their position. For instance, if promotions and raises seem to favor those who "play the game" over those who quietly deliver results, employees receive a clear signal about where to put their effort. Over time, an office culture can emerge where appearing productive is more important than being productive - a form of perverse natural selection where traits for actual efficiency are less selected than traits for visibility and self-promotion.

Bureaucratic Evolution and Job Replication

Organizations themselves exhibit evolutionary behavior. Over years and decades, corporations often develop bureaucratic structures that evolve and expand in predictable patterns, much like a growing organism. One classic observation, Parkinson's Law, states that "work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion," but even more pointedly, that in any bureaucracy, the number of employees grows at a steady rate regardless of the amount of work to be done. Cyril Northcote Parkinson, examining the British Civil Service, noted humorously (but with data) that certain departments kept hiring and growing even as their core duties shrank. In a famous example, the British Colonial Office reached its largest staff size at the very moment the British Empire had virtually no colonies left - the office was folded into another agency only after it hit peak employment with hardly any work left to justify it. Parkinson calculated a formula for bureaucratic expansion and identified its drivers: (1) "An official wants to multiply subordinates, not rivals," and (2) "Officials make work for each other." These two forces create a kind of organizational replication mechanism. Managers naturally prefer to hire more staff (thus expanding their empire) rather than streamline (which might threaten their role), and once new employees are on board, they generate interdependent work - reports, approvals, meetings - for one another. The net effect is that departments can multiply like cells dividing, regardless of whether the "organism" (the company) truly needs them to.

This evolutionary view helps explain the creation of roles that are "sustainable" in form, regardless of necessity. Just as a species might develop a costly ornament or redundant trait if it doesn't hinder survival, companies can accumulate vestigial positions or redundant layers that persist because they don't face immediate selection pressure. A job might originally be created to solve a temporary problem, but once it exists, the person in that role will seek to adapt and redefine the job to continue. They may take on new tasks, however marginal, to avoid obsolescence. Soon, that temporary role becomes permanent - and may spawn additional roles. For example, a task force formed to handle an exceptional situation might become a new department that then looks for new "missions" to justify itself. In evolutionary terms, the role has successfully found a niche and will fight to keep it. Indeed, sociologists have observed that formal organizations tend to take on "a life of their own beyond their formal objective," exhibiting a "tendency of bureaucratic organizations to perpetuate themselves." These structures, once established, will often keep lurching on without ever achieving their stated goal, because their real goal becomes simply to carry on regardless.

Anthropologist David Graeber's work on "bullshit jobs" offers a striking illustration of this phenomenon in modern workplaces. He defines a "bullshit job" as "a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though...the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case." Such jobs often arise in bloated corporate or governmental bureaucracies, and they persist because eliminating them is not straightforward in the system. Entire categories of work - for instance, excessive layers of middle management, or administrative roles created to fulfill bureaucratic compliance that no one actually reads - can proliferate. The people in those roles may privately sense the dubious nature of their work, yet they participate in the collective pretension of necessity. This aligns with our evolutionary analogy: once a "species" of job emerges in the organizational ecosystem, it can continue as long as it isn't lethal to its host. In fact, some of these jobs might serve an internal function by reinforcing hierarchy or providing comfort of control, even if they add no value to output. They survive because they attach themselves to the corporate organism's defense mechanisms - for example, by arguing that removing them would incur risks, break compliance, or reduce oversight. Like a parasitic gene that doesn't kill its host, such a job spreads and maintains itself within the corporate DNA.

We also see adaptation in bureaucratic practices. If a new technology or process threatens to make a job redundant, often the job's duties will simply shift to more complex or ambiguous tasks that are harder to measure, thereby preserving the need for that role. An analogy in nature would be an organism under threat that evolves a new defense - the job evolves new responsibilities (e.g. extra layers of approval, new internal metrics to track) that keep it essential. This is why efforts to streamline or "trim the fat" in organizations can meet fierce resistance or result in minimal change: the bureaucracy adapts to the reform, sometimes co-opting the very changes meant to curtail it. It's reminiscent of how bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics; bureaucracies evolve resistance to efficiency drives. Unless there is sustained pressure, the default evolutionary trajectory of offices is toward more complexity and self-maintenance.

Human Nature and Workplace Survival Instincts

The endurance of self-serving job structures is not just an abstract organizational quirk - it's rooted in human psychology. Evolutionary psychology suggests that our workplace behaviors today are deeply influenced by ancient survival drives. In a prehistoric environment, being expelled from the tribe could be a death sentence, so humans evolved a strong fear of social exclusion and a drive for security. In the office, this manifests as employees placing enormous value on job security - the modern analogue of securing one's place in the tribe. People will go to great lengths to avoid the "social death" of losing their job. This helps explain why employees sometimes resist efficiency improvements that could jeopardize their position. Even if a new software could automate half of one's tasks, a common reaction is to find new tasks or argue for the importance of human oversight, rather than gladly embrace the efficiency and risk becoming redundant. The instinctual calculus is clear: better to preserve the resource (the job) that guarantees survival (income, status) than to increase output at one's own expense.

Behavioral economics adds that humans are loss-averse - we disproportionately fear losses more than we value equivalent gains. In corporate life, the loss of status or employment looms far larger than the gain of increased company profit or even personal reward for exceptional performance. This can lead to conservative, protectionist behaviors. For example, a project manager might deliberately pad timelines or budgets, not to waste money, but to create a cushion that ensures nothing goes wrong on their watch. This cushion, however, is a form of inefficiency that the system tacitly tolerates because it also ensures the manager's unit doesn't fail (which in turn ensures the manager's job remains safe). Many employees also shy away from volunteering ideas that could dramatically improve efficiency if it means eliminating tasks that occupy their day. It's not (just) laziness or incompetence - often it's an unconscious alignment with an evolutionary impulse: avoid being the foolish gazelle that runs ahead of the herd into unknown territory. Within companies, that territory might be a new process or a radical idea that, if not fully supported, could backfire on the proposer's career. Thus, adaptation in the workplace often means aligning with behaviors that are tried-and-true for survival, even if they are suboptimal for performance.

Organizational theory also recognizes these human factors. Group dynamics and institutional norms exert pressure on individuals to conform. Employees learn "how we do things here" - the unwritten rules that often prioritize bureaucracy over boldness. Psychologist Fathali Moghaddam has noted that inefficient bureaucracy often persists because people come to see its rituals as "how we should do things," creating a normative trap where following procedure is valued over outcomes. In such an environment, initiatives that would improve efficiency might violate local norms, and so employees stick to the inefficient routines that everyone deems proper. The culture effectively "selects for" compliance with internal norms. Over time, this can create what Gareth Morgan described in metaphorical terms as an "organization as a psychic prison," where employees' thinking is so shaped by the system's rules and politics that they cannot easily envision truly new ways to operate. They are, in a sense, captive to the evolutionary path the bureaucracy has taken.

Why Unnecessary Roles Thrive - and the Cost

From the above, it becomes clear why unnecessary or marginally useful jobs can thrive inside large organizations. Once created, such roles are defended by the people in them (self-interest) and often by the bureaucracy around them (since eliminating roles can be bureaucratically difficult and politically unpopular). There is also a form of mutualism at play: one low-utility role might support another. For instance, an internal compliance officer might generate reports that justify the work of a data analyst, who in turn produces metrics that validate the role of the compliance officer - a closed loop. Each role in the loop might be of dubious value when viewed in isolation, but together they create an ecosystem of work that consumes resources and produces the appearance of diligence. This resembles an evolutionarily stable strategy in biology, where a set of traits or behaviors persists because, as a group, they reinforce one another's survival, even if some traits are individually costly.

The creation of "sustainable" jobs regardless of necessity is also fueled by institutional isomorphism - organizations copying each other. If every big company now has, say, a "Chief Happiness Officer" or a specific layer of project review committees, others may implement the same, not wanting to appear lacking. This mimetic behavior can lead to industry-wide adoption of roles that no one has empirically proven to add value. Yet once they are commonplace, they become part of the accepted corporate landscape and are rarely questioned. The job holder, meanwhile, will naturally make efforts to show their impact (often via soft, qualitative outcomes that are hard to measure, like "improved synergy" or "awareness") - further entrenching the perception that the role is needed, even if the company functioned fine before it existed. In evolutionary analogy, the role has attached itself to the cultural DNA of organizations broadly, and as long as companies that carry this "gene" are not at a competitive disadvantage severe enough to kill them, the gene will propagate.

The cost of these dynamics, however, is significant. At the organizational level, carrying a lot of "dead weight" in terms of unnecessary processes or roles lowers overall efficiency and saps resources that could go into innovation or growth. It can also demoralize truly productive employees. High-performing individuals often recognize bureaucratic bloat and can become frustrated or disengaged if they feel output is not rewarded while theatrics and self-preservation are. There is a cultural cost: a company inundated with self-sustaining bureaucratic jobs may become less agile, less creative, and less appealing to mission-driven talent. The "survival first" culture can crowd out a "mission first" culture. In evolutionary terms, if the environment changes - say the market tightens or disruption occurs - organizations that have long optimized for internal survival might find themselves ill-adapted to external challenges. The very traits that kept the bureaucracy safe (slowness, conservatism, complexity) make it poorly suited to compete or adapt quickly. This is akin to how a species highly specialized to a stable niche may flourish for a time, but struggles when the ecosystem shifts.

Aligning Evolution With Efficiency: Rethinking Incentives and Culture

Understanding these evolutionary analogies is not just an academic exercise - it offers insights into how we might re-tune corporate environments so that survival instincts align with organizational performance. If the problem is that employees and jobs evolve to prioritize their own security, the solution lies in redesigning the environment and incentives so that the safest path is also the most productive one. In other words, we want a workplace ecosystem where genuinely value-adding behaviors are also the ones that get "selected for" in terms of career survival and advancement.

One approach is to realign incentives and metrics to focus on outcomes rather than outputs or mere activity. Many firms have moved toward objective-based performance evaluations (e.g. OKRs - Objectives and Key Results) to tie an employee's fate to clear results. The key is to ensure that job security and progression depend on contributing to the mission more than on performing bureaucratic rituals. If employees see that solving a problem that eliminates their own tedious tasks will earn them a promotion (because it saved the company money), they are far more likely to take that initiative. Conversely, if they see that holding onto a legacy process provides no advantage to their career, they may willingly let it go. In evolutionary terms, this is changing the selection pressures: making inefficiency disadvantageous to survival and making innovation and efficiency advantageous. Organizations can, for example, reward teams for reducing unnecessary steps or streamlining themselves out of certain duties - perhaps by then moving those employees into more creative or strategic roles. This alleviates the fear that doing the right thing will eliminate one's job. In fact, enlightened organizations sometimes explicitly promise that no one will be laid off as a result of efficiency improvements, precisely to counteract the natural fear that holds back self-streamlining. When people trust that their future in the company is secure, they are more likely to care about the future of the company itself. Research has shown that increasing employees' sense of job security encourages them to invest more in improving their work and the organization's outcomes. It shifts the mindset from short-term self-preservation to long-term collective success.

Another strategy is to simulate evolutionary competition within the organization in a healthy way. This can be done by periodically rotating roles, merging departments, or challenging teams to justify their existence through internal "marketplaces." For instance, some companies allocate internal budgets that departments must "earn" by pitching their value to the company's strategy each year. This creates a selective pressure where units that cannot clearly demonstrate their necessity either reform or get reabsorbed elsewhere. The goal is not to foster cutthroat competition, but to ensure a dynamic equilibrium where the organization doesn't stagnate. By injecting a bit of natural selection (backed by thoughtful oversight to prevent chaos), companies can prevent bureaucratic niches from becoming too comfortable. It keeps every role oriented toward providing real value, or else evolving into one that does.

From a cultural perspective, leadership plays a crucial role in setting norms that counteract pure self-serving survival behavior. Leaders who openly value candor, reward risk-taking (even when it fails, if done in pursuit of the company's objectives), and who themselves avoid empire-building send a signal that the organization's "genes" should code for cooperation and performance, not for siloed self-interest. Some organizations have tackled this by limiting hierarchical layers and span of control, to reduce the opportunity for managers to accumulate excess staff. Others implement cross-functional teams and project-based work, so that people are continually realigning to new goals (making it harder to build a permanent fiefdom that exists just to exist).

It's also important to address the human psychological element: fostering a culture of trust and belonging can mitigate the worst excesses of survival anxiety. If employees feel that the company will take care of them in return for them taking care of the company's goals, the adversarial undercurrent (where each person quietly guards their own turf) diminishes. For example, offering retraining and internal mobility can turn the elimination of an outdated job from a personal crisis into an opportunity - the individual isn't cast out of the tribe, but rather given a new role in it. This approach echoes the evolutionary idea of adaptation: instead of going extinct, the "species" (the employee's career) evolves into a new niche within the company. Companies like AT&T, for instance, have invested heavily in reskilling programs for employees whose jobs are being automated, effectively evolving their workforce rather than trimming it. This helps maintain goodwill and a future-oriented mindset: employees see change as less of a threat and more of a natural progression, which in turn makes them more open to changes that improve efficiency.

Finally, organizations might reconsider what truly constitutes "fittest" in their context. In nature, fittest does not mean strongest in absolute terms; it means best suited to the environment. If the corporate environment rewards bureaucratic maneuvers, then indeed the fittest will be those who excel at that game. But if the environment (culture, incentives, leadership behavior) shifts to reward innovation, collaboration, and genuine productivity, then a different kind of employee behavior will become the new fittest. This could involve flattening certain hierarchies, cutting redundant approval steps, and using technology to increase transparency (so that real contributions are visible to all, not easily overshadowed by showmanship). With greater transparency, it's harder for a purely self-serving operator to take credit for others' work or to hide inefficiencies, thereby again changing the survival calculus.

Conclusion

Viewing corporate office jobs through the lens of biological evolution and natural selection offers a compelling explanation for why so many workplaces suffer from entrenched inefficiencies and self-perpetuating roles. Much like genes, some jobs seem to "want" to replicate and persist for their own sake, and like organisms, they adapt to their environment - which in this case is the company's culture and structure. Employees, being human, carry their evolutionary heritage into the office, often behaving in ways that prioritize personal survival (job security, status) even if it doesn't maximize output. The result can be an organizational ecosystem where keeping things alive (processes, roles, routines) becomes more important than making things better.

However, by understanding these tendencies, we are better equipped to manage them. We can strive to design organizations where evolutionary and economic incentives converge towards true productivity - where the "fittest" employees are those who actually further the company's mission, and where jobs that outlive their usefulness are gracefully retired or transformed rather than protected as endangered species. This might involve tough cultural shifts and rethinking reward systems, but the payoff is a more vibrant, adaptive organization. In such an organization, the only things that self-perpetuate are values and goals, not needless bureaucracy. Just as a well-adapted organism thrives by being in harmony with its environment, a well-adapted company can thrive by aligning the instincts of its people and structures with the genuine purpose of the enterprise. In the end, evolutionary success in business should be measured not by mere survival, but by sustainable value and growth, with each role justified by necessity and each employee secure because they contribute meaningfully - not merely because they've found a clever way to stick around.

Sources

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. (Analogy applied to corporate roles in text.)

- Pournelle, J. Iron Law of Bureaucracy: those who prioritize the bureaucracy's survival dominate.

- Parkinson, C.N. Parkinson's Law: bureaucracy expands 5-7% annually "irrespective of any variation in the amount of work (if any) to be done"; officials create subordinates and work for each other.

- "Self-licking ice cream cone" metaphor: a self-perpetuating system with no purpose beyond its own sustainment.

- Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit Jobs: concept of pointless jobs that survive via pretence of necessity.

- Korn Ferry/Workhuman survey (2024): 32% of employees and 37% of managers admit to faking productivity to appear busy.

- Evolutionary psychology research: Stable, secure work environments motivate employees to care about long-term outcomes (Griskevicius et al., 2012).

- Moghaddam, F. (2021). The Psychology of Bureaucracy: norms and narratives sustaining inefficient bureaucracy (discussion in text).

- Morgan, G. (1986). Images of Organization: organizations as organisms and cultures (metaphors informing analysis in text).

- Additional organizational theory on self-perpetuation and oligarchy, and examples of bureaucratic inertia.